Dante Alighieri, il Sommo Poeta

Posted on October 8th, 2013 by Anna in Uncategorized | No Comments »

No conversation about Italy or Italian culture can ever be complete without a mention of Dante Alighieri. Born Durante degli Alighieri in 13th century Florence, he is known universally to this day simply as Dante. In Italy, 700 years later, he also goes by the name il Sommo Poeta, or “the Supreme Poet,” or sometimes even just il Poeta, as Shakespeare is just “the Bard.” Dante’s legacy has transcended beyond the literary realm and into legend. Indeed, Modernist poet T.S. Eliot once stated, “Dante and Shakespeare divide the world between them. There is no third.”

Dante was born on the cusp of a political schism, when Florence was divided between two factions: the Ghibelines, who supported the regency of the Holy Roman Emperor, and the Guelphs, who supported the Papacy. Dante and all the rest of his family were fervent Guelphs—later White Guelphs, when the Guelphs themselves fractured—which strongly influenced his poetry and his public life until he died.

Married at 12 to Gemma di Manetto Donati, Dante’s lifelong love (despite the fact that he barely ever spoke to her,) was for a girl named Beatrice Portinari, whom he saw in the street once and decided to name his muse. (This was actually quite common in pre-Renaissance Italy, with unrequited courtly love being all the rage.) As it was, Beatrice fueled a series of love sonnets and served as the semi-divine guide through Heaven in Dante’s final work, Paradiso.

Moreover, she provided the inspiration for Dante’s involvement in Italy’s first literary movement, il Dolce Stil Novo (sweet new style,) a term which he coined. In a society where all “high” literature was meant to be composed in Latin, Dante and his contemporaries, Guido Cavalcanti and Guido Guinizzelli, pioneered a poetic style that was intellectual and refined—and written in their native Tuscan. Through strong use of metaphor and lyricism, advocates of the Dolce Stil Novo focused on the themes of Amore and Gentilezza—Love and Noble-Mindedness—coupled with blind adoration of female beauty. His experiments with this style, as well as his one-sided love story with Beatrice, he documented in his short work, La Vita Nuova.

But of course, while he was a prolific writer in other areas, Dante’s fame comes from his magnum opus, literature’s greatest work of biblical fanfiction, The Divine Comedy, known in Italian simply as La Commedia. Describing Dante’s allegorical journey through the afterlife as described by the medieval Church, The Divine Comedy is viewed to this day as a triumph of poetry, Christian theology, and philosophy. It’s also filled with symbolism and numerology, with precedence being given to the numbers 3 and 9. It’s divided into three books, Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso, and each book is divided into 33 cantos plus one introduction, to make up 100 cantos each. There are nine circles of Hell, nine levels of Purgatory, and then nine spheres of Heaven, et cetera.

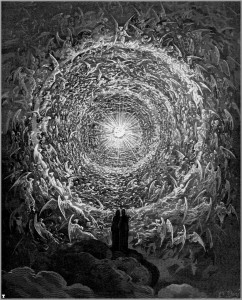

Guided by the Roman poet Virgil through Hell, Dante takes a tour of Limbo, each of the seven deadly sins, and finally the lair of Satan at the very bottom. (Unsurprisingly, many of Dante’s political opponents—Black Guelphs, Pope Boniface VIII, and Cante de’ Gabrielli di Gubbio who exiled him from Florence—make appearances as damned souls undergoing various torments in Hell.) They ascend through Purgatory, and then to Paradise, where Dante is passed off to Beatrice who guides him through the heavenly spheres, the four cardinal virtues and the three theological virtues, until at the apex of Heaven he finally looks on the face of God.

While Dante enjoyed a brief popularity after his death, his poetry fell out of fashion for a few hundred years until they were revived by the Romantic movement and declared to be works of singular genius. Since then, Dante has been beloved by litterateurs worldwide, with many scholars deliberately taking a lifetime to read The Divine Comedy, saving Paradiso until the end of the career when they have sufficient wisdom to take it on. In Italy they practically swear by his name, and Florence has spent the past 700 years trying to get his remains back from Ravenna, where he’s buried. But whether you’re a Dante fanatic or not, it’s impossible to deny the lasting impression he’s had on western literature, culture, and philosophy.